Blog posts:

Feb. 28, 2023: Machine learning ratings of politicians’ tweets for dishonorable speech

Oct. 10, 2022: 5 udemy.com courses on raising your self-esteem ranked

Oct. 3, 2022: Other attempts out there to rate politicians’ tweets for negativity

Sep. 29, 2022: Alaska’s 2022 U.S. senate candidates’ tweets rated for negativity, other measures

Sep. 29, 2022: Arizona’s 2022 U.S. senate candidates’ tweets rated for negativity, other measures

Sep. 29, 2022: Georgia’s 2022 U.S. senate candidates’ tweets rated for negativity, other measures

Sep. 29, 2022: Nevada’s 2022 U.S. senate candidates’ tweets rated for negativity, other measures

Sep. 29, 2022: Pennsylvania’s 2022 U.S. senate candidates’ tweets rated for negativity, other measures

Sep. 29, 2022: Wisconsin’s 2022 U.S. senate candidates’ tweets rated for negativity, other measures

Sep. 28, 2022: Updated: 2022 U.S. senate candidates’ tweets rated for negativity, other measures

Sep. 27, 2022: Top 10 reasons to buy my book (in my opinion)

Sep. 16, 2022: 3 new dishonorable speech ratings, updated

Sep. 5, 2022: What you get from my “Honorable Speech” book that you don’t from this website

Sep. 5, 2022 (edited Sep. 6, 2022): Gifting my “Honorable Speech” book to politicians

Jul. 25, 2022: 2022 U.S. senate candidates’ tweets rated for negativity, other measures

Jul. 25, 2022: eBook on honorable speech available for pre-order

May 12, 2022: 11 Udemy anger management courses ranked best to worst (in my opinion)

Apr. 15, 2022: 22 things you may say that destroy the most value in the world

Apr. 14, 2022 (edited Apr. 17, 2022): Ranking actions and words by how much value they destroy

Apr. 8, 2022 (edited Apr. 13, 2022): Trump vs. Biden vs. H. Clinton: 3 new dishonorable speech ratings in action

Apr. 6, 2022: 14 kinds of dishonorable speech I believe politicians (too) commonly use

Apr. 4, 2022: 3 new dishonorable speech ratings

Mar. 30, 2022: The difference between an honorable speech culture and a politically correct one

Mar. 3, 2022: How to honorably accuse someone of having done something bad

Mar. 2, 2022: What is personal responsibility? Why is it so important? And what tends to build or destroy it?

Feb. 28, 2022: What is love (the non-romantic kind)?

Feb. 10, 2022: The damages of gossip, rumors and conspiracy theories

Feb. 7, 2022: Why we may or may not believe unsubstantiated accusations against someone

Feb. 4, 2022: The damages of leveling and value inversion

Feb. 1, 2022: The damages of blame and excuses

Jan. 29, 2022: How to speak honorably about people who’ve done or allegedly done bad things

Jan. 28, 2022: Why speak honorably about people who’ve done or allegedly done bad things

Jan. 12, 2022: How can we inspire politicians to speak (and act) more honorably?

Jan. 10, 2022: Some on the Right and the Left use dehumanizing terms: examples and damages

Jan. 6, 2022: 6 Reasons to love people who are driven by hate

Dec. 31, 2021: Why honor the office of the president?

Dec. 21, 2021: Framework for determining dishonor in humor

Nov. 7, 2021: Possible hate behind calling someone a social justice warrior (SJW)

Oct. 28, 2021: What is civil discourse and how is it different from honorable discourse?

Oct. 28, 2021: Why is civil/honorable discourse important?

Oct. 28, 2021: What you could focus on to help you speak more civilly/honorably with people you disagree with

Oct. 24, 2021: How to go from social justice warrior (SJW) to true justice lover

Oct. 19, 2021: 10 ways to help reduce the influence of online negativity

Oct. 13, 2021: How to know if you’re doing something out of hate or love

Oct. 4, 2021: Speaking honorably is speaking kindly

Aug. 18, 2021: How does speaking honorably uphold the building of value in the world?

Aug. 17, 2021: Update to my definition of “value”

Jul. 6, 2021: 7 possible misconceptions about speaking honorably

Jul. 5, 2021: 5 reasons to call out dishonorable speech on your side and 3 reasons not to

Jul. 2, 2021: 10 things you can do to make your speech more honorable

Jul. 1, 2021: When is it honorable to say negative things?

Jun. 30, 2021: 9 possible damages of offering opinion as fact

Jun. 1, 2021: 11 reasons you may want to speak honorably

May 10, 2021: Guide to @NPelosiHon and @KMcCarthyHon “suggested more honorable version” Twitter accounts:

Apr. 15, 2021: 5 reasons you may want to care that politicians speak more honorably

Dec. 6, 2020: 10 common reasons people speak dishonorably

Nov. 11, 2020: 5 reasons to speak honorably about Donald Trump (even if you hate him)

Feb. 28, 2023:

Machine learning ratings of politicians’ tweets for dishonorable speech

On Feb. 1, the official Twitter account for this website, @DishonorP, started tweeting out machine learning-obtained dishonorable speech ratings of some politicians’ tweets. The plan is to continue tweeting out new ratings every Wednesday.

The machine learning models for rating politicians’ tweets on misrepresenting reality/misleading, promoting entitlement/victimhood, and negativity are still being refined, but here are a few details on them:

- The ConvBERT transformer from HuggingFace was used in Python to build separate machine learning models for each dishonorable speech rating

- The data used to train the models was from manual ratings of 16 different U.S. Senate candidates’ tweets from March 15-May 15, 2022, plus tweets from @SpeakerPelosi and @SpeakerMcCarthy (formerly @GOPLeader) from May 10-Oct. 10, 2021. A significantly smaller number of tweets in the dataset came from a number of other congress people’s accounts searched specifically for words related to entitlement and blame

Oct. 10, 2022:

5 udemy.com courses on raising your self-esteem ranked

I’m going to share with you my rankings of 5 courses offered through udemy.com on raising one’s self-esteem. I purchased all 5 courses on sale, at prices ranging from $11.99 to $15.99, although current full prices range from $34.99 to $99.99.

Here are my rankings, in order of which I liked best to which I liked least:

- “Create Healthy Self-Esteem from within Yourself” by T.J. Guttormsen

- “Intro – 6 Keys to Ultimate Confidence, Body, and Self-Esteem” by Dr. Elisaveta Pavlova

- “Self-Esteem Masterclass: Learn to Love Yourself” by Leon Chaudhari

- “Increase Core Confidence and Self-Esteem in Record Time” Jimmy Naraine

- “Reclaiming Your Positive Self-Esteem” Terry L. Ledford

I wouldn’t say any of these courses aren’t worth buying, especially when on sale – I think there are things people are going to find helpful in each of them. My favorite of the five, though, was “Create Healthy Self-Esteem from within Yourself” by T.J. Guttormsen. What I really liked about Guttormsen’s course was that he talked about taking responsibility and following your own morals as ways to raise your self-esteem, which I agree with, and I’ll go into more in a moment.

First, maybe we should define “self-esteem.” merriam-webster.com defines it as a confidence and satisfaction in oneself: self-respect. This seems generally in line with what I think of when I think of high “self-esteem,” which is consistently feeling good about oneself. To me, “satisfaction in oneself” and “self-respect,” from merriam webster’s definition, imply feeling good about oneself. Since I believe we’re all ultimately in control of our own emotions, we could just choose to feel good about and love and respect ourselves in any moment. Boom, instant high self-esteem! But I think it’s a little more difficult than it sounds because most of us aren’t very good at consistently choosing to love and feel good about ourselves in every moment. And I think self-esteem, or satisfaction in oneself, is actually more involved than that, because, yes, I can choose to feel good about myself in any moment, but if I did a bad thing in the world, my conscience is still there in the background saying, “Hey, buddy, actually, you can’t feel 100% good about yourself because I’m here to remind you you have some unresolved business to attend to. Take responsibility, and try to heal the damage of your actions, though, and we can be good again.”

So, I believe, if we’re choosing in each moment to feel good about and love ourselves, which involves taking responsibility for our emotions, and we have a clear conscience from taking responsibility for our effects in the world (and within ourselves), then we can have what I’d call high “true” self-esteem.

Regarding responsibility, some of the courses I evaluated talked about techniques that, in my view, effectively help you control your emotional state, but they didn’t loop back and mention how these were basically ways of taking responsibility for your emotions. Some such techniques include reframing, being curious rather than judgmental, and feeling good about yourself through self-affirmations. So I feel like those courses would be helpful, but they likely won’t get you all the way there because of the lack of emphasis on personal responsibility as key to truly raising your self-esteem.

I hope this ranking of self-esteem-building courses was useful to you – thank you for reading.

Oct. 3, 2022:

Other attempts out there to rate politicians’ tweets for negativity

In writing up the results of my analyses on U.S. senate candidates’ tweets for dishonorable speech, I came across an interesting article in which machine learning was used to rate some U.S. senators’ tweets for negativity over an approximately two-month period before the 2018 elections. In the article, they said 4 humans looked for 4 factors in tweets: negative tone, personal attacks, policy attacks and incivility. The authors then used this data to train their machine learning model to identify the same things. They also mention a few other studies in which humans manually identified negativity in tweets. A significant advantage of a well-trained machine learning system is that it should allow tweets by politicians to be rated very quickly without a large expenditure of resources. Alessandro Nai, one of the authors of the study, published some of their results to what he called “The Negative Campaigning Comparative Expert Survey” on his website, although there’s no data for 2022.

I believe if lwv.org and ballotpedia.org started posting these sorts of machine learning-obtained negativity ratings for tweets on their websites as part of candidate profiles, this could provide valuable information to citizens who could vote for candidates with lower tweet negativity scores and thus support a reduction in negativity in political discourse.

Sep. 29, 2022:

Alaska’s 2022 U.S. senate candidates’ tweets rated for negativity, other measures

This is a copy of a press release:

Website Releases U.S. Senate Candidate for Alaska Tweet Ratings

DishonorableSpeechInPolitics.com releases dishonorable speech ratings of Alaska’s 2022 U.S. senate candidates Lisa Murkowski’s and Kelly Tshibaka’s tweets

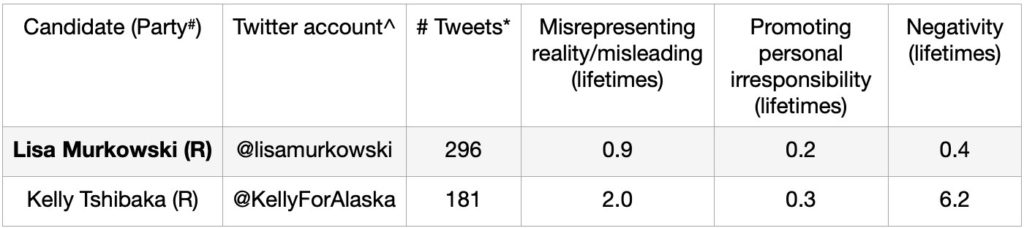

Halfmoon, NY, Sept. 29, 2022 – DishonorableSpeechInPolitics.com has released dishonorable speech ratings of tweets over a two-month period for Alaska’s 2022 U.S. senate candidates Republican Lisa Murkowski and Republican Kelly Tshibaka. The three ratings include those for misrepresenting reality and misleading, promoting personal irresponsibility, and negativity.

The Google Chrome extension Twlets was used to capture tweets from March 15 to May 15, 2022, which was well before primary elections were held on August 16. The analyses to obtain the ratings were performed by identifying which of 37 categories of dishonorable speech were thought to be present in each tweet, and counting up the “years” of dishonorable speech “sentence” from each one. In analogy with the criminal justice system in which sentences are handed out as a number of years or a lifetime in prison for various offenses, this rating system hands out suggested “sentences” in “years” or “lifetimes” (taken as 60 “years”) for dishonorable speech. More years are added to the ratings for speech offenses deemed more severe or damaging, and fewer years for speech considered less damaging. For instance, calling someone names results in a significantly higher number of years of sentence than offering opinion as fact. The lower the number of years or lifetimes of a rating, the more honorable the speech.

The ratings and how they’re obtained are described in more detail at DishonorableSpeechInPolitics.com, and even more detail in Sean M. Sweeney’s new book “Honorable Speech: What Is It, Why Should We Care, and Is It Anywhere to Be Found in U.S. Politics?,” available at amazon.com.

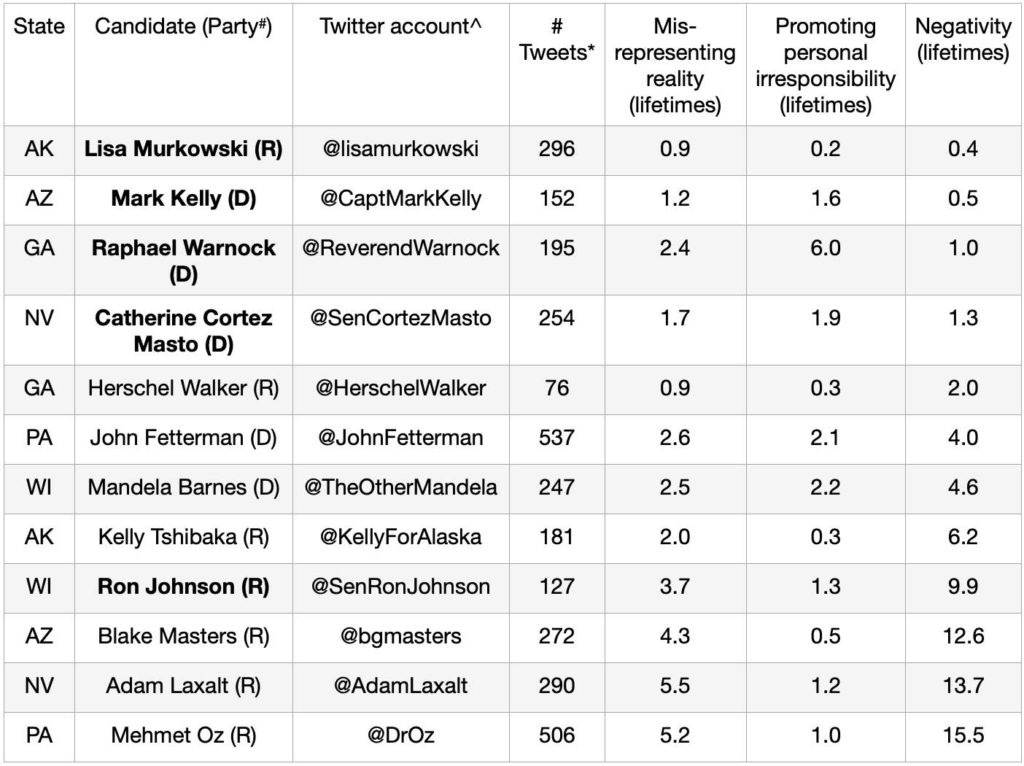

Results of the analyses are listed in the table below.

Dishonorable speech ratings of Alaska’s 2022 U.S. senate candidates’ Twitter accounts over the period from March 15 to May 15, 2022. Incumbent is listed in bold.

#R = Republican, D = Democrat

^When candidates had more than one Twitter account, the one with the most followers was used for this analysis.

*Includes retweets, not replies.

Tshibaka’s Twitter negativity rating was about 14 times higher than Murkowski’s.

The table below lists the dishonorable speech categories that were main contributors to the negativity ratings of Murkowski’s and Tshibaka’s tweets.

Murkowski’s tweets were assessed as containing negativity aimed at the following, on these number of occasions:

Tshibaka’s tweets were assessed as containing negativity aimed at the following, on these number of occasions:

The biggest contributors to the promoting personal irresponsibility ratings were promoting entitlement and victimhood for Murkowski, and blaming for Tshibaka.

The misrepresenting reality and misleading rating likely doesn’t correspond to what some may intuitively think it might, i.e., simple fact checking of what someone says (although that would be a part of it.) For instance, offering opinion as fact, misrepresenting reality through logical fallacies, calling someone names (which effectively offers opinion as fact), and blaming others (misleading by denying one’s own share of responsibility) all contribute to this rating. The misrepresenting reality and misleading rating could perhaps be thought of as a measure of how much a politician is trying to sell their side of a story rather than holistically presenting how reality is to the best of their understanding of it.

If these sorts of ratings of politicians’ communications became widespread, they could help voters make more informed decisions at the polls to support candidates who share their values.

References used in the analyses:

About Dishonorable Speech Consulting, LLC

Founded by PhD engineer Sean M. Sweeney, Dishonorable Speech Consulting, LLC launched its DishonorableSpeechInPolitics.com website in Oct., 2020. The site is dedicated to increasing honorable speech in politics and the world in general. In Sept., 2022, Sean released his book “Honorable Speech: What Is It, Why Should We Care, and Is It Anywhere to Be Found in U.S. Politics?” on amazon.com. Twitter: @DishonorP

###

Sep. 29, 2022:

Arizona’s 2022 U.S. senate candidates’ tweets rated for negativity, other measures

This is a copy of a press release:

Website Releases U.S. Senate Candidate for Arizona Tweet Ratings

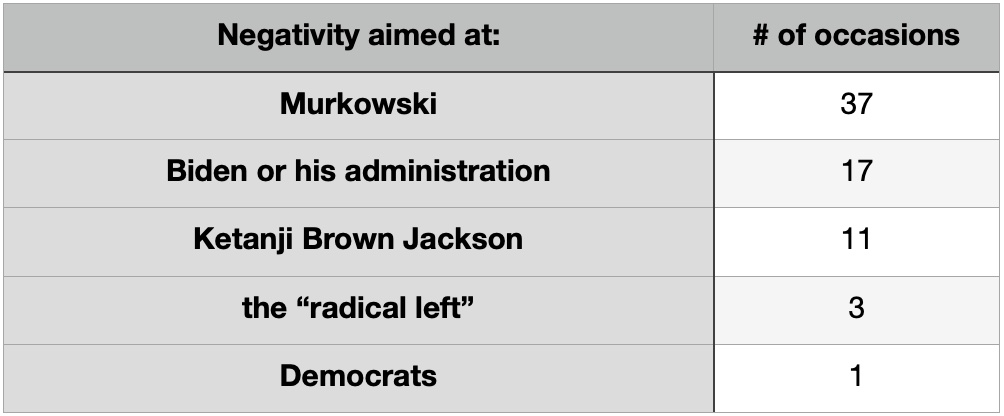

DishonorableSpeechInPolitics.com releases dishonorable speech ratings of Arizona’s 2022 U.S. senate candidates Mark Kelly’s and Blake Masters’ tweets

Halfmoon, NY, Sept. 29, 2022 – DishonorableSpeechInPolitics.com has released dishonorable speech ratings of tweets over a two-month period for Arizona’s 2022 U.S. senate candidates Democrat Mark Kelly and Republican Blake Masters. The three ratings include those for misrepresenting reality and misleading, promoting personal irresponsibility, and negativity.

The Google Chrome extension Twlets was used to capture tweets from March 15 to May 15, 2022, which was well before primary elections were held on August 2. This means that Blake Masters, in particular, had not yet been selected as the Republican nominee. The analyses to obtain the ratings were performed by identifying which of 37 categories of dishonorable speech were thought to be present in each tweet, and counting up the “years” of dishonorable speech “sentence” from each one. In analogy with the criminal justice system in which sentences are handed out as a number of years or a lifetime in prison for various offenses, this rating system hands out suggested “sentences” in “years” or “lifetimes” (taken as 60 “years”) for dishonorable speech. More years are added to the ratings for speech offenses deemed more severe or damaging, and fewer years for speech considered less damaging. For instance, calling someone names results in a significantly higher number of years of sentence than offering opinion as fact. The lower the number of years or lifetimes of a rating, the more honorable the speech.

The ratings and how they’re obtained are described in more detail at DishonorableSpeechInPolitics.com, and even more detail in Sean M. Sweeney’s new book “Honorable Speech: What Is It, Why Should We Care, and Is It Anywhere to Be Found in U.S. Politics?,” available at amazon.com.

Results of the analyses are listed in the table below.

Dishonorable speech ratings of Arizona’s 2022 U.S. senate candidates’ Twitter accounts over the period from March 15 to May 15, 2022. Incumbent is listed in bold.

#R = Republican, D = Democrat

^When candidates had more than one Twitter account, the one with the most followers was used for this analysis.

*Includes retweets, not replies.

Masters’ Twitter negativity rating was about 26 times that of Kelly.

The table below lists the dishonorable speech categories that were main contributors to the negativity ratings of Kelly’s and Masters’ tweets.

Kelly’s tweets were assessed as containing negativity aimed at the following, on these number of occasions:

Masters’ tweets were assessed as containing negativity aimed at the following, on these number of occasions:

In addition, Masters’ tweets were assessed as containing negativity towards AOC, Netflix, Taylor Lorenz, Jeff Bezos, the FBI, Mitt Romney, congress, Mark Zuckerberg, the CIA, justices in a particular court case, China, Cory Booker and Stephen King on one occasion each.

The biggest contributors to the promoting personal irresponsibility ratings were promoting entitlement and victimhood for Kelly, and blaming for Masters.

The misrepresenting reality and misleading rating likely doesn’t correspond to what some may intuitively think it might, i.e., simple fact checking of what someone says (although that would be a part of it.) For instance, offering opinion as fact, misrepresenting reality through logical fallacies, calling someone names (which effectively offers opinion as fact), and blaming others (misleading by denying one’s own share of responsibility) all contribute to this rating. The misrepresenting reality and misleading rating could perhaps be thought of as a measure of how much a politician is trying to sell their side of a story rather than holistically presenting how reality is to the best of their understanding of it.

If these sorts of ratings of politicians’ communications became widespread, they could help voters make more informed decisions at the polls to support candidates who share their values.

References used in the analyses:

About Dishonorable Speech Consulting, LLC

Founded by PhD engineer Sean M. Sweeney, Dishonorable Speech Consulting, LLC launched its DishonorableSpeechInPolitics.com website in Oct., 2020. The site is dedicated to increasing honorable speech in politics and the world in general. In Sept., 2022, Sean released his book “Honorable Speech: What Is It, Why Should We Care, and Is It Anywhere to Be Found in U.S. Politics?” on amazon.com. Twitter: @DishonorP

###

Sep. 29, 2022:

Georgia’s 2022 U.S. senate candidates’ tweets rated for negativity, other measures

This is a copy of a press release:

Website Releases U.S. Senate Candidate for Georgia Tweet Ratings

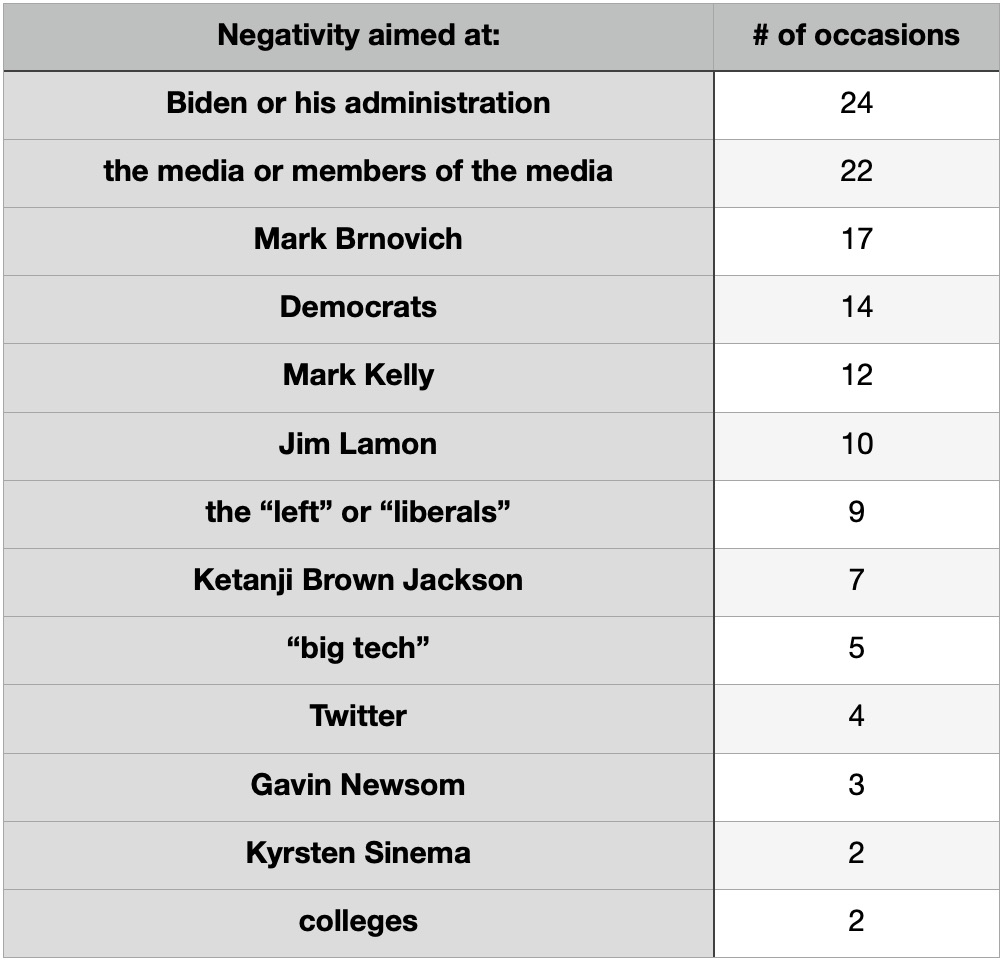

DishonorableSpeechInPolitics.com releases dishonorable speech ratings of Georgia’s 2022 U.S. senate candidates Raphael Warnock’s and Herschel Walker’s tweets

Halfmoon, NY, Sept. 29, 2022 – DishonorableSpeechInPolitics.com has released dishonorable speech ratings of tweets over a two-month period for Georgia’s 2022 U.S. senate candidates Democrat Raphael Warnock and Republican Herschel Walker. The three ratings include those for misrepresenting reality and misleading, promoting personal irresponsibility, and negativity.

The Google Chrome extension Twlets was used to capture tweets from March 15 to May 15, 2022, which was before primary elections were held on May 24. The analyses to obtain the ratings were performed by identifying which of 37 categories of dishonorable speech were thought to be present in each tweet, and counting up the “years” of dishonorable speech “sentence” from each one. In analogy with the criminal justice system in which sentences are handed out as a number of years or a lifetime in prison for various offenses, this rating system hands out suggested “sentences” in “years” or “lifetimes” (taken as 60 “years”) for dishonorable speech. More years are added to the ratings for speech offenses deemed more severe or damaging, and fewer years for speech considered less damaging. For instance, calling someone names results in a significantly higher number of years of sentence than offering opinion as fact. The lower the number of years or lifetimes of a rating, the more honorable the speech.

The ratings and how they’re obtained are described in more detail at DishonorableSpeechInPolitics.com, and even more detail in Sean M. Sweeney’s new book “Honorable Speech: What Is It, Why Should We Care, and Is It Anywhere to Be Found in U.S. Politics?,” available at amazon.com.

Results of the analyses are listed in the table below.

Dishonorable speech ratings of Georgia’s 2022 U.S. senate candidates’ Twitter accounts over the period from March 15 to May 15, 2022. Incumbent is listed in bold.

#R = Republican, D = Democrat

^When candidates had more than one Twitter account, the one with the most followers was used for this analysis.

*Includes retweets, not replies.

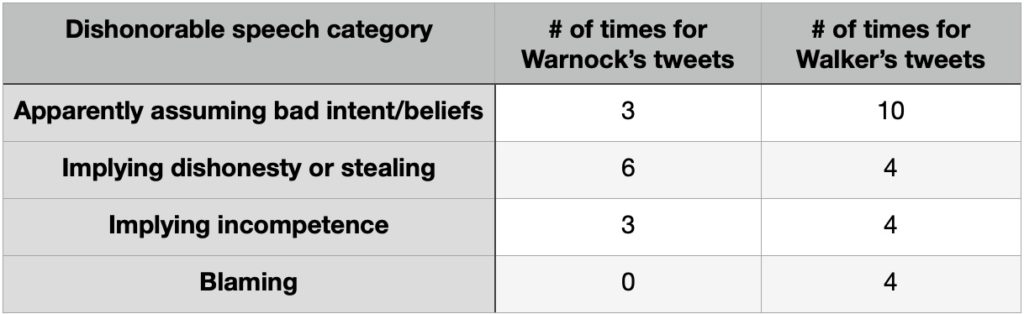

Walker’s Twitter negativity rating was twice that of Warnock.

The table below lists the dishonorable speech categories that were main contributors to the negativity ratings of Warnock’s and Walker’s tweets.

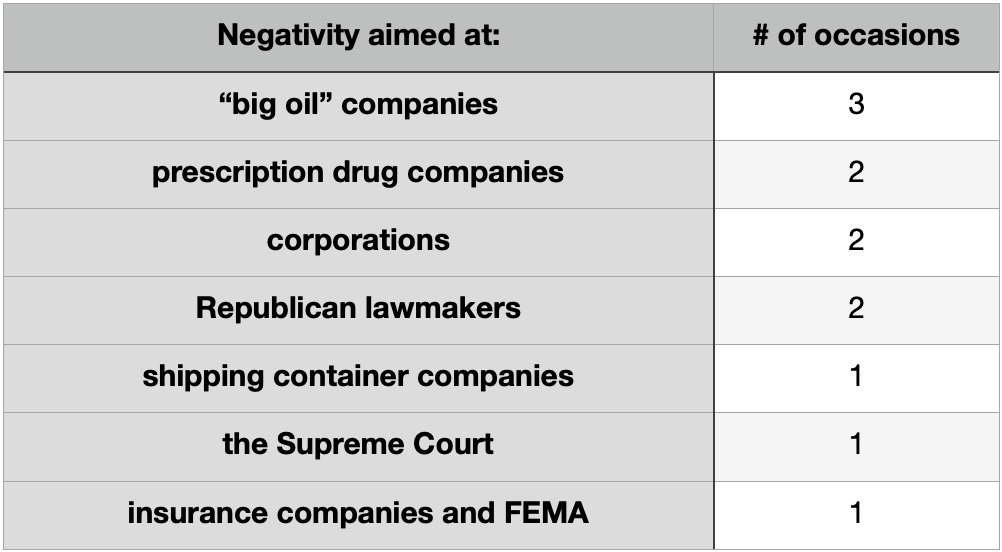

Warnock’s tweets were assessed as containing negativity aimed at the following, on these number of occasions:

Walker’s tweets were assessed as containing negativity aimed at the following, on these number of occasions:

The biggest contributors to the promoting personal irresponsibility ratings were promoting entitlement and victimhood for both Warnock and Walker, while blaming also contributed a little less than half to this rating for Walker’s tweets. Warnock promoted entitlement especially regarding capping insulin costs. This promoting of entitlement also contributed to his misrepresenting reality and misleading rating.

The misrepresenting reality and misleading rating likely doesn’t correspond to what some may intuitively think it might, i.e., simple fact checking of what someone says (although that would be a part of it.) For instance, offering opinion as fact, misrepresenting reality through logical fallacies, calling someone names (which effectively offers opinion as fact), and blaming others (misleading by denying one’s own share of responsibility) all contribute to this rating. The misrepresenting reality and misleading rating could perhaps be thought of as a measure of how much a politician is trying to sell their side of a story rather than holistically presenting how reality is to the best of their understanding of it.

If these sorts of ratings of politicians’ communications became widespread, they could help voters make more informed decisions at the polls to support candidates who share their values.

References used in the analyses:

About Dishonorable Speech Consulting, LLC

Founded by PhD engineer Sean M. Sweeney, Dishonorable Speech Consulting, LLC launched its DishonorableSpeechInPolitics.com website in Oct., 2020. The site is dedicated to increasing honorable speech in politics and the world in general. In Sept., 2022, Sean released his book “Honorable Speech: What Is It, Why Should We Care, and Is It Anywhere to Be Found in U.S. Politics?” on amazon.com. Twitter: @DishonorP

###

Sep. 29, 2022:

Nevada’s 2022 U.S. senate candidates’ tweets rated for negativity, other measures

This is a copy of a press release:

Website Releases U.S. Senate Candidate for Nevada Tweet Ratings

DishonorableSpeechInPolitics.com releases dishonorable speech ratings of Nevada’s 2022 U.S. senate candidates Catherine Cortez Masto’s and Adam Laxalt’s tweets

Halfmoon, NY, Sept. 29, 2022 – DishonorableSpeechInPolitics.com has released dishonorable speech ratings of tweets over a two-month period for Nevada’s 2022 U.S. senate candidates Democrat Catherine Cortez Masto and Republican Adam Laxalt. The three ratings include those for misrepresenting reality and misleading, promoting personal irresponsibility, and negativity.

The Google Chrome extension Twlets was used to capture tweets from March 15 to May 15, 2022, which was before primary elections were held on June 14. This means that Adam Laxalt, in particular, had not yet been selected as the Republican nominee. The analyses to obtain the ratings were performed by identifying which of 37 categories of dishonorable speech were thought to be present in each tweet, and counting up the “years” of dishonorable speech “sentence” from each one. In analogy with the criminal justice system in which sentences are handed out as a number of years or a lifetime in prison for various offenses, this rating system hands out suggested “sentences” in “years” or “lifetimes” (taken as 60 “years”) for dishonorable speech. More years are added to the ratings for speech offenses deemed more severe or damaging, and fewer years for speech considered less damaging. For instance, calling someone names results in a significantly higher number of years of sentence than offering opinion as fact. The lower the number of years or lifetimes of a rating, the more honorable the speech.

The ratings and how they’re obtained are described in more detail at DishonorableSpeechInPolitics.com, and even more detail in Sean M. Sweeney’s new book “Honorable Speech: What Is It, Why Should We Care, and Is It Anywhere to Be Found in U.S. Politics?,” available at amazon.com.

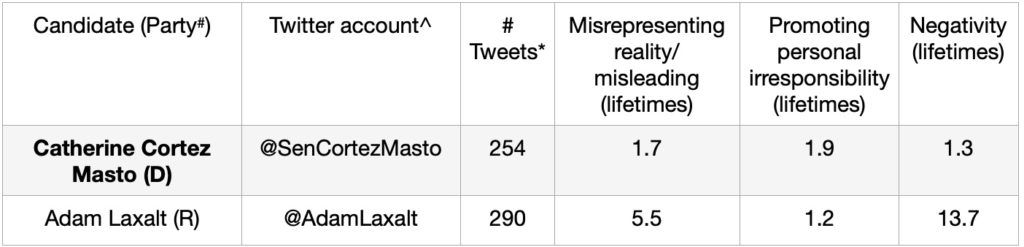

Results of the analyses are listed in the table below.

Dishonorable speech ratings of Nevada’s 2022 U.S. senate candidates’ Twitter accounts over the period from March 15 to May 15, 2022. Incumbent is listed in bold.

#R = Republican, D = Democrat

^When candidates had more than one Twitter account, the one with the most followers was used for this analysis.

*Includes retweets, not replies.

Cortez Masto’s Twitter negativity rating was more than 10 times less than Laxalt’s.

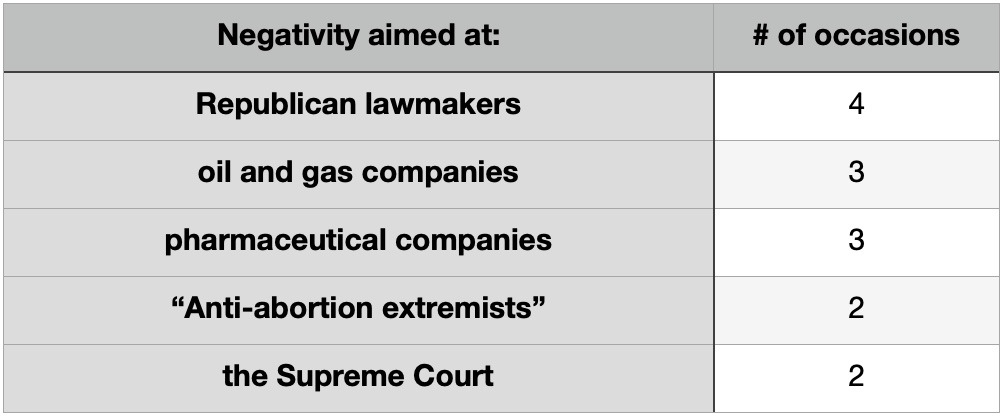

The table below lists the dishonorable speech categories that were main contributors to the negativity ratings of Cortez Masto’s and Laxalt’s tweets.

Cortez Masto’s tweets were assessed as containing negativity aimed at the following, on these number of occasions:

Laxalt’s tweets were assessed as containing negativity aimed at the following, on these number of occasions:

The biggest contributors to the promoting personal irresponsibility ratings were promoting entitlement and victimhood for Cortez Masto, and about half promoting entitlement and victimhood and half blaming for Laxalt.

The misrepresenting reality and misleading rating likely doesn’t correspond to what some may intuitively think it might, i.e., simple fact checking of what someone says (although that would be a part of it.) For instance, offering opinion as fact, misrepresenting reality through logical fallacies, calling someone names (which effectively offers opinion as fact), and blaming others (misleading by denying one’s own share of responsibility) all contribute to this rating. The misrepresenting reality and misleading rating could perhaps be thought of as a measure of how much a politician is trying to sell their side of a story rather than holistically presenting how reality is to the best of their understanding of it.

If these sorts of ratings of politicians’ communications became widespread, they could help voters make more informed decisions at the polls to support candidates who share their values.

References used in the analyses:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fKDfFp5hb80

About Dishonorable Speech Consulting, LLC

Founded by PhD engineer Sean M. Sweeney, Dishonorable Speech Consulting, LLC launched its DishonorableSpeechInPolitics.com website in Oct., 2020. The site is dedicated to increasing honorable speech in politics and the world in general. In Sept., 2022, Sean released his book “Honorable Speech: What Is It, Why Should We Care, and Is It Anywhere to Be Found in U.S. Politics?” on amazon.com. Twitter: @DishonorP

###

Sep. 29, 2022:

Pennsylvania’s 2022 U.S. senate candidates’ tweets rated for negativity, other measures

This is a copy of a press release:

Website Releases U.S. Senate Candidate for Pennsylvania Tweet Ratings

DishonorableSpeechInPolitics.com releases dishonorable speech ratings of Pennsylvania’s 2022 U.S. senate candidates John Fetterman’s and Mehmet Oz’s tweets

Halfmoon, NY, Sept. 29, 2022 – DishonorableSpeechInPolitics.com has released dishonorable speech ratings of tweets over a two-month period for Pennsylvania’s 2022 U.S. senate candidates Democrat John Fetterman and Republican Mehmet Oz. The three ratings include those for misrepresenting reality and misleading, promoting personal irresponsibility, and negativity.

The Google Chrome extension Twlets was used to capture tweets from March 15 to May 15, 2022, which was before primary elections were held on May 17. This means that Mehmet Oz, in particular, had not yet been selected as the Republican nominee. The analyses to obtain the ratings were performed by identifying which of 37 categories of dishonorable speech were thought to be present in each tweet, and counting up the “years” of dishonorable speech “sentence” from each one. In analogy with the criminal justice system in which sentences are handed out as a number of years or a lifetime in prison for various offenses, this rating system hands out suggested “sentences” in “years” or “lifetimes” (taken as 60 “years”) for dishonorable speech. More years are added to the ratings for speech offenses deemed more severe or damaging, and fewer years for speech considered less damaging. For instance, calling someone names results in a significantly higher number of years of sentence than offering opinion as fact. The lower the number of years or lifetimes of a rating, the more honorable the speech.

The ratings and how they’re obtained are described in more detail at DishonorableSpeechInPolitics.com, and even more detail in Sean M. Sweeney’s new book “Honorable Speech: What Is It, Why Should We Care, and Is It Anywhere to Be Found in U.S. Politics?,” available at amazon.com.

Results of the analyses are listed in the table below.

Dishonorable speech ratings of Pennsylvania’s 2022 U.S. senate candidates’ Twitter accounts over the period from March 15 to May 15, 2022.

#R = Republican, D = Democrat

^When candidates had more than one Twitter account, the one with the most followers was used for this analysis.

*Includes retweets, not replies.

Oz’s Twitter negativity rating was nearly four times as high as Fetterman’s.

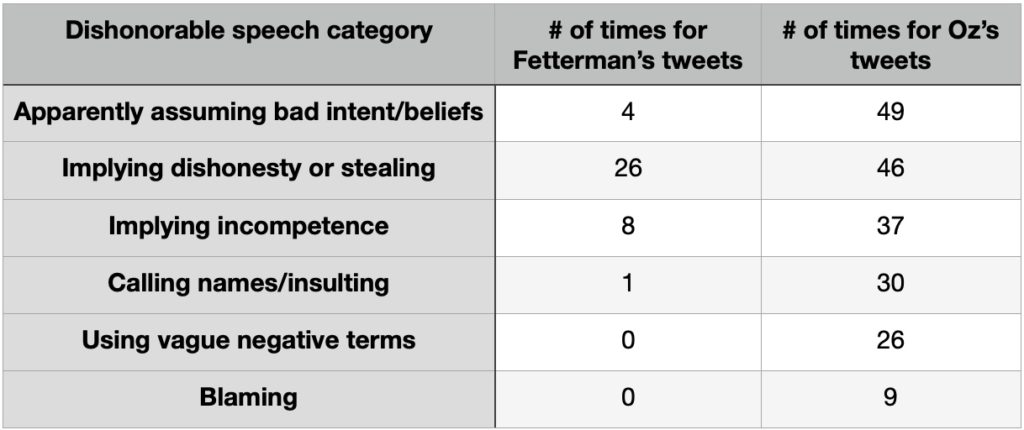

The table below lists the dishonorable speech categories that were main contributors to the negativity ratings of Fetterman’s and Oz’s tweets.

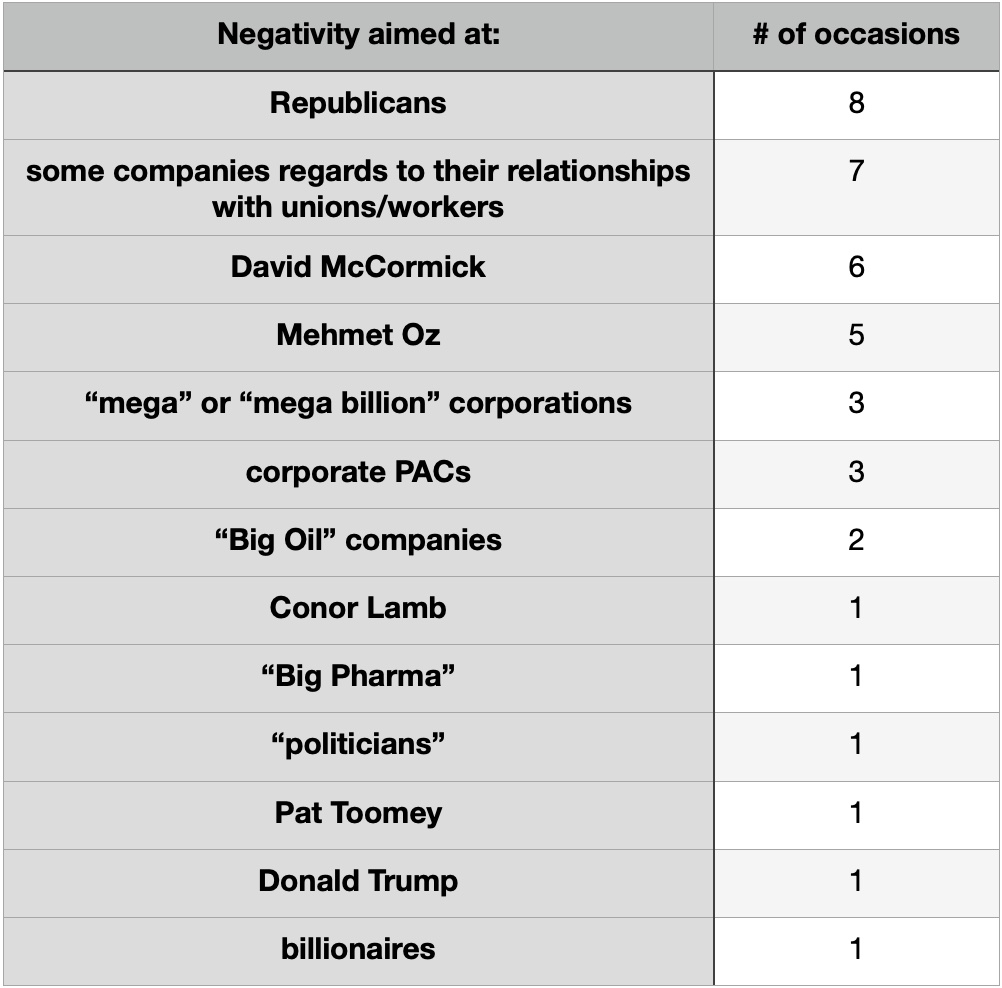

Fetterman’s tweets were assessed as containing negativity aimed at the following, on these number of occasions:

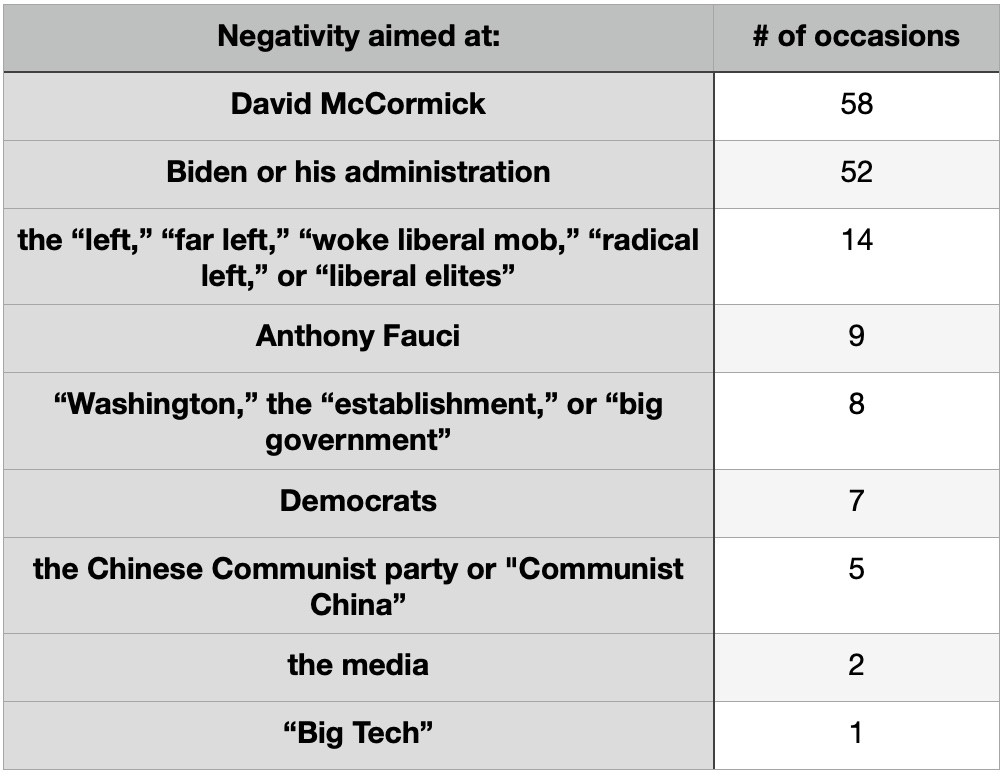

Oz’s tweets were assessed as containing negativity aimed at the following, on these number of occasions:

The biggest contributors to the promoting personal irresponsibility ratings were promoting entitlement and victimhood for both Fetterman and Oz, with about 30 percent of the rating coming from blaming for Oz’s tweets.

The misrepresenting reality and misleading rating likely doesn’t correspond to what some may intuitively think it might, i.e., simple fact checking of what someone says (although that would be a part of it.) For instance, offering opinion as fact, misrepresenting reality through logical fallacies, calling someone names (which effectively offers opinion as fact), and blaming others (misleading by denying one’s own share of responsibility) all contribute to this rating. The misrepresenting reality and misleading rating could perhaps be thought of as a measure of how much a politician is trying to sell their side of a story rather than holistically presenting how reality is to the best of their understanding of it.

If these sorts of ratings of politicians’ communications became widespread, they could help voters make more informed decisions at the polls to support candidates who share their values.

References used in the analyses:

https://educationdata.org/student-loan-debt-by-state; https://stacker.com/stories/1667/states-most-and-least-student-debt

https://www.cnn.com/2022/03/15/politics/energy-independence-fact-check/index.html

About Dishonorable Speech Consulting, LLC

Founded by PhD engineer Sean M. Sweeney, Dishonorable Speech Consulting, LLC launched its DishonorableSpeechInPolitics.com website in Oct., 2020. The site is dedicated to increasing honorable speech in politics and the world in general. In Sept., 2022, Sean released his book “Honorable Speech: What Is It, Why Should We Care, and Is It Anywhere to Be Found in U.S. Politics?” on amazon.com. Twitter: @DishonorP

###

Sep. 29, 2022:

Wisconsin’s 2022 U.S. senate candidates’ tweets rated for negativity, other measures

This is a copy of a press release:

Website Releases U.S. Senate Candidate for Wisconsin Tweet Ratings

DishonorableSpeechInPolitics.com releases dishonorable speech ratings of Wisconsin’s 2022 U.S. senate candidates Ron Johnson’s and Mandela Barnes’ tweets

Halfmoon, NY, Sept. 29, 2022 – DishonorableSpeechInPolitics.com has released dishonorable speech ratings of tweets over a two-month period for Wisconsin’s 2022 U.S. senate candidates Republican Ron Johnson and Democrat Mandela Barnes. The three ratings include those for misrepresenting reality and misleading, promoting personal irresponsibility, and negativity.

The Google Chrome extension Twlets was used to capture tweets from March 15 to May 15, 2022, which was well before primary elections were held on August 9. This means that Mandela Barnes, in particular, had not yet been selected as the Democratic nominee. The analyses to obtain the ratings were performed by identifying which of 37 categories of dishonorable speech were thought to be present in each tweet, and counting up the “years” of dishonorable speech “sentence” from each one. In analogy with the criminal justice system in which sentences are handed out as a number of years or a lifetime in prison for various offenses, this rating system hands out suggested “sentences” in “years” or “lifetimes” (taken as 60 “years”) for dishonorable speech. More years are added to the ratings for speech offenses deemed more severe or damaging, and fewer years for speech considered less damaging. For instance, calling someone names results in a significantly higher number of years of sentence than offering opinion as fact. The lower the number of years or lifetimes of a rating, the more honorable the speech.

The ratings and how they’re obtained are described in more detail at DishonorableSpeechInPolitics.com, and even more detail in Sean M. Sweeney’s new book “Honorable Speech: What Is It, Why Should We Care, and Is It Anywhere to Be Found in U.S. Politics?,” available at amazon.com.

Results of the analyses are listed in the table below.

Dishonorable speech ratings of Wisconsin’s 2022 U.S. senate candidates’ Twitter accounts over the period from March 15 to May 15, 2022. Incumbent is listed in bold.

#R = Republican, D = Democrat

^When candidates had more than one Twitter account, the one with the most followers was used for this analysis.

*Includes retweets, not replies.

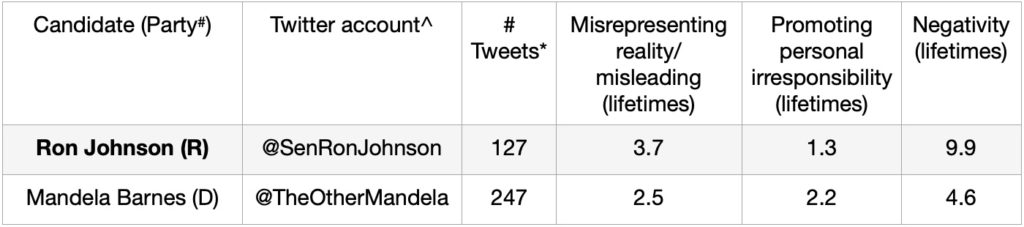

Johnson’s Twitter negativity rating was about double that of Barnes.

The table below lists the dishonorable speech categories that were main contributors to the negativity ratings of Johnson’s and Barnes’ tweets.

Johnson’s tweets were assessed as containing negativity aimed at the following, on these number of occasions:

In addition, Johnson’s tweets were assessed as containing negativity towards Chuck Schumer, the Washington Post, the CDC, Twitter, Medicaid administrators, Politifact, some school districts, the FDA and NIH, and the Secret Service on one occasion each.

Barnes’ tweets were assessed as containing negativity aimed at the following, on these number of occasions:

In addition, Barnes’ tweets were assessed as containing negativity towards “Big Tech,” lawmakers who’ve “sold out American manufacturing,” former governor Scott Walker, senators who trade stocks while in office, and Amazon on one occasion each.

The biggest contributors to the promoting personal irresponsibility ratings were blaming and then promoting entitlement and victimhood for Johnson, and promoting entitlement and victimhood for Barnes.

The misrepresenting reality and misleading rating likely doesn’t correspond to what some may intuitively think it might, i.e., simple fact checking of what someone says (although that would be a part of it.) For instance, offering opinion as fact, misrepresenting reality through logical fallacies, calling someone names (which effectively offers opinion as fact), and blaming others (misleading by denying one’s own share of responsibility) all contribute to this rating. The misrepresenting reality and misleading rating could perhaps be thought of as a measure of how much a politician is trying to sell their side of a story rather than holistically presenting how reality is to the best of their understanding of it.

If these sorts of ratings of politicians’ communications became widespread, they could help voters make more informed decisions at the polls to support candidates who share their values.

References used in the analyses:

https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2022/04/08/unraveling-tale-hunter-biden-35-million-russia/

https://www.yahoo.com/video/u-senator-says-may-true-233002349.html

https://nypost.com/2022/05/09/white-house-condemns-attack-on-anti-abortion-group-office/

About Dishonorable Speech Consulting, LLC

Founded by PhD engineer Sean M. Sweeney, Dishonorable Speech Consulting, LLC launched its DishonorableSpeechInPolitics.com website in Oct., 2020. The site is dedicated to increasing honorable speech in politics and the world in general. In Sept., 2022, Sean released his book “Honorable Speech: What Is It, Why Should We Care, and Is It Anywhere to Be Found in U.S. Politics?” on amazon.com. Twitter: @DishonorP

###

Sep. 28, 2022:

Updated: 2022 U.S. senate candidates’ tweets rated for negativity, other measures

This is a copy of an upcoming press release:

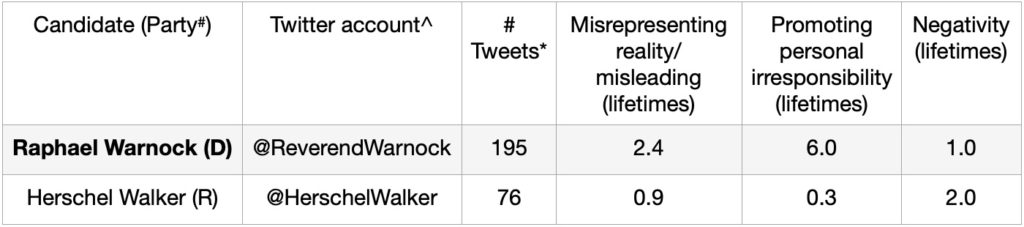

DishonorableSpeechInPolitics.com has released dishonorable speech ratings of tweets over a two-month period from twelve 2022 U.S. senate candidates’ Twitter accounts. The Republican and Democrat candidates come from six states: Alaska, Arizona, Georgia, Nevada, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin. The candidates’ tweets were rated on three areas: 1) misrepresenting reality and misleading, 2) promoting personal irresponsibility, and 3) negativity.

The Google Chrome extension Twlets was used to capture tweets from March 15 to May 15, 2022, which was before primary elections were held in any of the six states. The analyses to obtain the ratings were performed by identifying which of 37 categories of dishonorable speech were thought to be present in each tweet, and counting up the “years” of dishonorable speech “sentence” from each one. In analogy with the criminal justice system in which sentences are handed out as a number of years or a lifetime in prison for various offenses, this rating system hands out suggested “sentences” in “years” or “lifetimes” (taken as 60 “years”) for dishonorable speech. More years are added to the ratings for speech offenses deemed more severe or damaging, and fewer years for speech considered less damaging. For instance, calling someone names results in a significantly higher number of years of sentence than offering opinion as fact. The lower the number of years or lifetimes of a rating, the more honorable the speech.

The ratings and how they’re obtained are described in more detail at DishonorableSpeechInPolitics.com, and even more detail in Sean M. Sweeney’s new book “Honorable Speech: What Is It, Why Should We Care, and Is It Anywhere to Be Found in U.S. Politics?,” available at amazon.com.

Results of the analyses are listed in the table below. Of the candidates examined, Alaska Republican Lisa Murkowski’s tweets had the best rating for negativity over the two-month time period, while Pennsylvania Republican Mehmet Oz’s tweets had the worst.

Dishonorable speech ratings of six states’ 2022 U.S. senate candidates’ Twitter accounts over the period from March 15 to May 15, 2022, sorted from least to most negative. Incumbents are listed in bold.

#R = Republican, D = Democrat

^When candidates had more than one Twitter account, the one with the most followers was used for this analysis.

*Includes retweets, not replies.

Main contributors to the negativity ratings tended to be tweets assessed as implying dishonesty or stealing, implying incompetence, apparently assuming bad intent or beliefs, using vague negative terms such as “radical left,” and containing blame. Some of the common topics Democrats’ tweets were negative on were Republicans and corporations (“Big Oil,” “Big Pharma,” etc.). Some of the common topics Republicans’ tweets were negative on included President Biden or his administration, the media, Democrats, and the “Left.”

The biggest contributors to the promoting personal irresponsibility rating tended to be blaming and promoting entitlement and victimhood, with Democrats tending to do more of the latter than Republicans.

Offering opinion as fact and misrepresenting reality through logical fallacies both tended to contribute significantly to the misrepresenting reality and misleading rating. This rating likely doesn’t correspond to what some may intuitively think it might, i.e., simple fact checking of what someone says (although that would be a part of it.) For instance, calling someone names (which effectively offers opinion as fact), and blaming others (misleading by denying one’s own share of responsibility) both contribute to this rating. The misrepresenting reality and misleading rating could perhaps be thought of as a measure of how much a politician is trying to sell their side of a story rather than holistically presenting how reality is to the best of their understanding of it.

If these sorts of ratings of politicians’ communications became widespread, they could help voters make more informed decisions at the polls to support candidates who share their values.

References used in these analyses of U.S. senate candidates’ tweets:

For Mandela Barnes:

For Mark Brnovich:

For John Fetterman:

https://educationdata.org/student-loan-debt-by-state; https://stacker.com/stories/1667/states-most-and-least-student-debt

For Sarah Godlewski:

https://www.ronjohnson.senate.gov/2014/4/johnson-comments-on-paycheck-fairness-vote

For Ron Johnson:

https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2022/04/08/unraveling-tale-hunter-biden-35-million-russia/

https://www.yahoo.com/video/u-senator-says-may-true-233002349.html

https://nypost.com/2022/05/09/white-house-condemns-attack-on-anti-abortion-group-office/

For Alex Lasry:

For Adam Laxalt:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fKDfFp5hb80

For Blake Masters:

For Lisa Murkowski:

For Mehmet Oz:

https://www.cnn.com/2022/03/15/politics/energy-independence-fact-check/index.html

For Herschel Walker:

Sep. 27, 2022:

Top 10 reasons to buy my book (in my opinion)

10. Because you’re genuinely interested in the answers to the questions in the title of the book: “Honorable Speech: What Is It, Why Should We Care, and Is It Anywhere to Be Found in U.S. Politics?”

9. To read some of the content that’s not on my website such as about the excuses people make for speaking dishonorably, the benefits of changing the attitudes behind dishonorable speech such as a win-at-all-costs mentality, and 10 things you can do to proactively make your speech more honorable, not just less dishonorable.

8. To use as a resource for teaching students about speaking honorably and recognizing dishonorable speech in politics.

7. Because you want to learn how to make your own speech more honorable.

6. To take the 30-Day Challenge to speaking more honorably in written form with embedded links rather than through my YouTube videos.

5. To help support a system in which people with good intent trying to do good in the world can make money off of it, thus incentivizing more good action by them and others.

4. To help this work get noticed – Amazon publishes the sales ranks of books and a better ranking is going to make the book seem more legitimate and intriguing to others. (Oh, and while you’re at it, following my Facebook page and Twitter and YouTube accounts couldn’t hurt either.)

3. Because you’re interested in knowing the details of my dishonorable speech rating system that you can’t find on my website.

2. To gift to a politician with a note saying you’d like to see them speaking more honorably, such as is described in the book (see my blog post on how to do this for an ebook).

1. Because you’re disillusioned with the current political culture and want to better understand how a quantitative dishonorable speech rating system might help change that.

Sep. 16, 2022:

3 new dishonorable speech ratings, updated

On April 4, 2022, I introduced three new dishonorable speech ratings, including for: 1) avoiding misrepresenting reality and misleading, 2) avoiding promoting personal irresponsibility, and 3) avoiding negativity. More recently, as part of writing my “Honorable Speech: What Is It, Why Should We Care, and Is It Anywhere to Be Found in U.S. Politics?” book, I revamped these ratings somewhat, dropping the word “avoiding” to start each rating title, so they’re now called: 1) misrepresenting reality and misleading, 2) promoting personal irresponsibility, and 3) negativity.

I also changed how the ratings were calculated. Instead of putting all of a given dishonorable speech category as part of one of the ratings, I split the “sentence” values in “years” of each category so that, for instance, category #1 name calling may have 1 year that goes towards misrepresenting reality and misleading (since it’s effectively offering opinion as fact, in my opinion), while the rest of the years for this category go under the negativity rating. I believe doing this results in the 3 new ratings more accurately representing their respective fractions of the overall dishonorable speech. For details on how the years for each dishonorable speech category are split into these updated ratings, see my book. Also note that lower numbers of “years” for these ratings indicates that the speech is more honorable, i.e., a lower rating is better.

It’s worth mentioning, I believe, that the misrepresenting reality and misleading rating doesn’t correspond to what some may intuitively think it would, i.e., simple fact checking of what someone says – although that is part of it. For instance, offering opinion as fact, misrepresenting reality through logical fallacies, calling someone names (which effectively offers opinion as fact), and blaming others (misleading by denying one’s own share of responsibility) all contribute to this rating. This rating could perhaps be thought of as a measure of how much a politician is trying to sell their side of a story rather than holistically presenting how reality is to the best of their understanding of it.

Sep. 5, 2022:

What you get from my “Honorable Speech” book that you don’t from this website

- My quantitative dishonorable speech ratings system laid out in detail

- Dishonorable quotes from a range of U.S. presidential candidates for you to guess who said them

- Some new sections that are neither on my blog nor my YouTube channel such as about the excuses people make for speaking dishonorably, the benefits of changing some of the attitudes behind dishonorable speech such as a win-at-all-costs mentality, and 10 additional things you can do to make your speech more honorable

- Humor to break up the heaviness of the subject

- “Training materials” for doing dishonorable speech analyses

- My 30-day challenge to speak more honorably, in written form (it’s also on my YouTube channel, in video form)

- More polished versions of some of my blog posts

- Some edited scripts from my YouTube videos that aren’t on my blog, such as about being respectful and about dishonor in children’s stories

- The joy of supporting someone trying to do good in the world by paying for a product they’ve put out

Sep. 5, 2022:

Gifting my “Honorable Speech” book to politicians

I’ve recently completed a book: “Honorable Speech: What Is It, Why Should We Care, and Is It Anywhere to Be Found in U.S. Politics.” In it, one of the ways I mention to try to help encourage U.S. politicians to campaign less negatively and speak more honorably is to gift them a copy of my eBook. If we had enough people do this, I believe it would send a strong message. On amazon.com, if you send someone a link to an eBook, and it isn’t redeemed within 60 days, you’re not charged. My thought is that most politicians probably aren’t going to redeem more than one or perhaps a few copies of the book for their staff. So if we had a ton of people sending them links, most of those people likely wouldn’t actually end up paying for the book, but the message would still get conveyed that they cared enough to be willing to pay to get their point across.

I’ll now walk you through the steps to order eBooks for politicians of your choice:

- You can find my eBook listed at this link on amazon.com,

- Find the “Buy for others” box off to the right (it’s below the “Buy now” box), and hit “Buy for others,”

- Under “Choose your delivery method,” select “We’ll give you redemption links to send to your recipients”

- Select the quantity of links that you want,

- Hit “Place your order” and you’ll receive an email with a “Manage eBook” button that you can click on that will take you to your links

- Click on “Copy link with instructions,” and it will copy the eBook link plus instructions on how to redeem it onto your clipboard which you can then paste into an email or as a message on a politicians’ website contact page,

- Send a link to a given politician by going to their website and sending them the link plus redemption instructions through their contact form, with a message of your choice.

Here’s a suggested message:

Dear (insert politician’s name),

Please accept this gift of Sean M. Sweeney’s eBook “Honorable Speech: What Is It, Why Should We Care, and Is It Anywhere to Be Found in U.S. Politics.” See instructions for redeeming it below.

I’m a concerned citizen and would like to see more honorable speech by our politicians, such as less negative campaigning. I hope this book is useful to you to better your understanding of what it means to speak honorably, and that you may incorporate this into how you communicate. Thank you for your time.

Sincerely,

(your name)

P.S. For ethics rules purposes: I’m not a registered federal lobbyist, foreign agent, or entity that employs or retains a registered federal lobbyist or foreign agent, and this eBook is valued at $6.99.

(insert the redeemable link plus instructions here)

For an example of a politician’s contact page, here’s one for President Joe Biden:

https://www.whitehouse.gov/contact/

It does take a little of your time to go through this process, but I believe it’s a relatively simple thing that if enough people did for enough politicians, we may begin to change the nature of political discourse in the U.S.

Jul. 25, 2022:

2022 U.S. senate candidates’ tweets rated for negativity, other measures

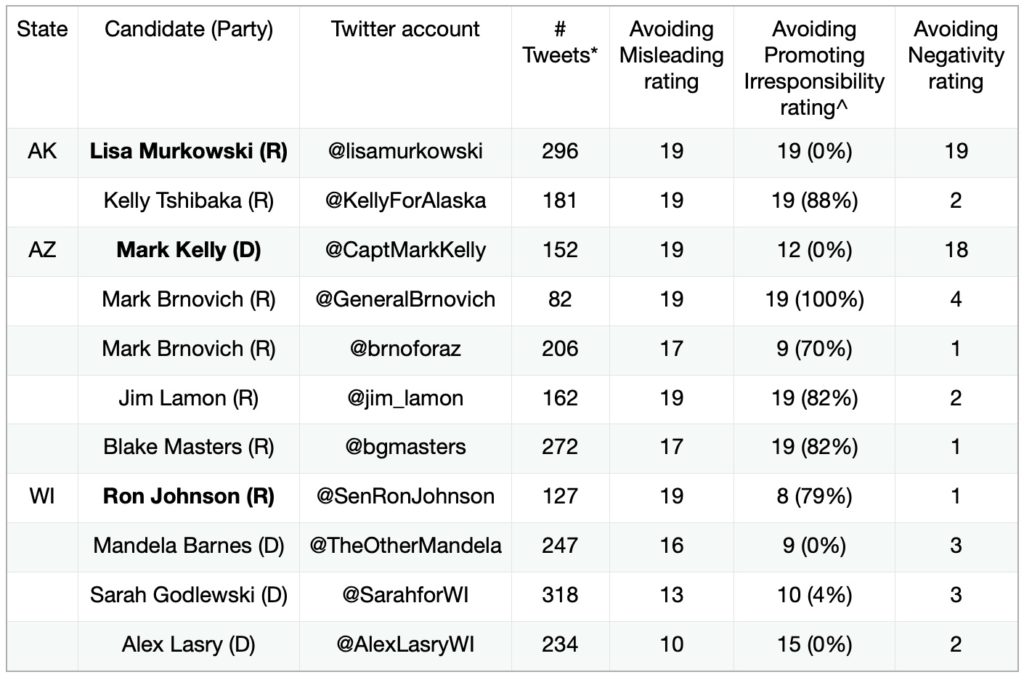

Dishonorablespeechinpolitics.com has released honorable speech ratings of some 2022 U.S. senate candidates’ tweets over the period of March 15 to May 15, 2022. These include some of the leading candidates in the polls (according to racetothewh.com and projects.fivethirtyeight.com) for the upcoming primary elections in Arizona (August 2), Wisconsin (August 9) and Alaska (August 16). Three honorable speech ratings were determined for each candidate, including for: 1) avoiding misrepresenting reality/misleading, 2) avoiding promoting personal irresponsibility, and 3) avoiding negativity. The ratings scales range from 1 to 20, with 20 being the best, meaning no dishonorable speech was identified. As a general guide, ratings of 16 to 19 could be considered good, 10 to 15 fair, 5 to 9 poor, and 1 to 4 highly dishonorable. 37 categories of dishonorable speech were used to analyze the tweets, see dishonorablespeechinpolitics.com/Services/#Categories for more details on these. More details about the rating system can be found here.

In this case of analyzing tweets, the 1 to 20 scale for avoiding negativity was set by considering the number of days of tweets (62) divided by the “suggested dishonorability sentence” in years for negativity (see dishonorablespeechinpolitics.com/Services/#RatingSystem for more on “suggested dishonorability sentences”). The highest score of this type among these candidates was set equal to 19, and the lowest equal to 1, with a linear scale used in between. The 1 to 20 scales for avoiding misrepresenting reality/misleading and avoiding promoting personal irresponsibility were then set by doubling the slope of the scale for avoiding negativity. This was done since approximately a factor of two fewer categories of dishonorable speech are involved in these other two ratings than in the rating for avoiding negativity.

For candidates with multiple Twitter accounts, the account with the most followers was analyzed. Since the ratings are based on how much dishonorable speech there was per day, not how much there was per tweet, accounts with fewer tweets may tend to score better – fewer tweets per day means fewer words to possibly contain dishonorable speech per day. For Mark Brnovich, his @GeneralBrnovich account had more followers, but significantly fewer tweets than his @brnoforaz account during this two month time period (82 tweets for @GeneralBrnovich versus 206 tweets for @brnoforaz). For him, both of his accounts were analyzed.

Incumbents Lisa Murkowski, a Republican, and Mark Kelly, a Democrat, had the most honorable speech in their tweets over the two month time period analyzed, according to the ratings. Incumbent Ron Johnson, a Republican, had one of the worst ratings of the candidates analyzed.

Ratings for avoiding misrepresenting reality/misleading were generally high, with some candidates offering opinion as fact and/or taking quotes from their opponents out of context. While Democrats tended to promote personal irresponsibility (such as by supporting entitlement to healthcare) more than Republicans, Ron Johnson, a Republican, received the lowest score in that category, mostly due to blaming Democrats for issues Republicans share some responsibility in. Over this relatively small group of candidates, there seemed to be either very little negativity (ratings of 18 or 19) or a lot of it (ratings of 4 or less), with not much in between.

Honorable speech ratings of some 2022 U.S. senate candidates’ Twitter accounts. Incumbents are listed in bold.

*Includes retweets, not replies. ^Percentage of rating due to blaming shown in parentheses.

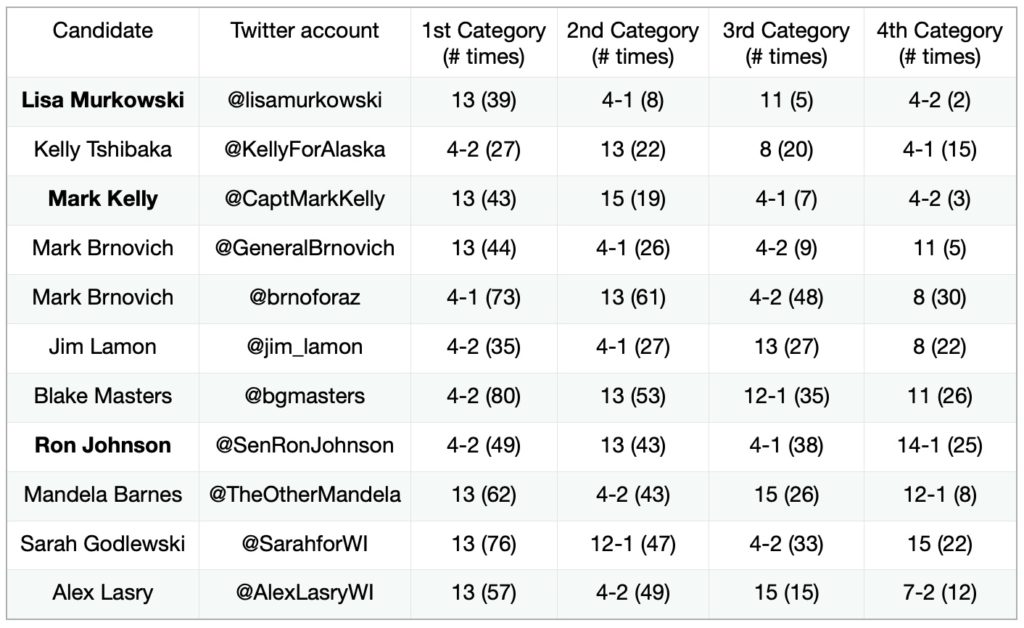

For each candidate, the first 4 most common categories of dishonorable speech and how many times they were identified in that candidates’ tweets are listed in the second table below. The most commonly identified dishonorable speech categories under the avoiding negativity rating were #4-2 implying wrongdoing, #4-1 implying incompetence, #12-1 assuming bad intent or beliefs, and #8 using vague negative terms such as “extremist” and “radical.”

The Google Chrome extension Twlets was used to extract tweets to a spreadsheet for these analyses.

The 4 most commonly identified categories of dishonorable speech for each candidates’ tweets, and the number of times they were identified.

Quick guide to categories:

4-1 = implying incompetence

4-2 = implying stealing/dishonesty

7-2 = misquoting to imply someone’s a bad person

8 = using vague negative terms

11 = misrepresenting reality (as through logical fallacies)

12-1 = assuming bad intent or beliefs

13 = offering opinion as fact

14-1 = blaming for things you are partially responsible for

15 = promoting entitlement/victimhood

Polls examined:

Arizona polls: https://www.racetothewh.com/arizona,

Wisconsin polls: https://www.racetothewh.com/senate/wisconsin,

Alaska polls: https://projects.fivethirtyeight.com/polls/alaska/.

Jul. 25, 2022:

eBook on honorable speech available for pre-order

My forthcoming ebook, “Honorable Speech: What Is It, Why Should We Care, and Is It Anywhere to Be Found in U.S. Politics?,” is now available for pre-order for $6.99 on amazon, for its Sept. 5, 2022 release. Here is the book description:

This book isn’t about political correctness or punishing people into talking a certain way.

Instead, it’s an attempt to inspire people, including our political leaders, to speak more honorably, or in a way that ultimately supports love and value building over hate and value destruction. And it provides a guide for how people may go about doing that.

A detailed dishonorable speech rating system is presented, including examples of its use to quantify the damages of speeches, tweets and campaign commercials by U.S. politicians, in particular, presidential and senate candidates. Some ideas are set forward on how each of us may help break the pattern of partisan-based dishonorable speech in the U.S.

May 12, 2022:

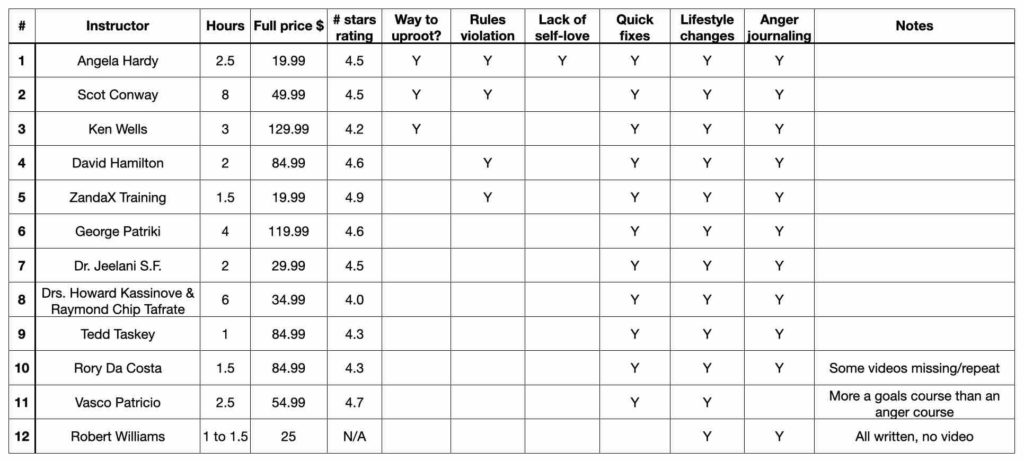

11 Udemy anger management courses ranked best to worst (in my opinion)

I’ve been reading books and taking courses on personal development for years. Today I’m going to share my rankings of 11 anger management courses I purchased on sale from udemy.com for prices ranging from $12.99 to $24.99. Based on my personal development experiences, here are some of the key things I was looking for in an anger management, or more preferably, anger elimination course:

- You get angry from not getting what you want and/or a “rule violation”

- “Rule violation” anger ultimately comes from a lack of self-love

- We can eliminate, not just manage our anger by going through a defined process

An example of a rule you may have is: you should be considerate of others. When people don’t seem to be considerate, rule violation anger may result because the other person’s behavior shows you a part of yourself you hate, that is, the inconsiderate part. But the thing is, we all have that inconsiderate part in us, and keeping a rule about it doesn’t somehow “fix” it, it really just lets anger control you.

Some of the other things I looked for that these online courses covered included:

- “Quick fix” anger management techniques such as breathing while counting, walking away to compose oneself, and emotional state changes

- Lifestyle changes to make anger reactions less likely such as exercise and meditation

- Anger journaling or writing down some things about your anger

- Tips for communicating when angry

- Becoming more aware of your anger and its accompanying signs

- Anger comes from you, it’s not caused by what happens in the outside world

- Underneath anger is fear

- Expectations can lead to anger

Here then is my ranking of the courses, with some of what they covered or didn’t:

My top-ranked course is the one by Angela Hardy because it not only includes changing one’s rules to eliminate anger responses, it talks about self-love and gives a method called Emotional Freedom Technique tapping, or EFT tapping, to increase self-love. Her course is only $19.99 even when it’s not on sale, and, in my opinion, it’s definitely worth this price and more. My second favorite was the one by Scot Conway in which he uses some of Anthony Robbins’ techniques such as emotional state changes and changing one’s rules to eliminate anger. And my third favorite was the one by Ken Wells which includes what I found to be a useful perception management worksheet for reducing or eliminating specific anger responses. If you can buy two or even all three of these courses on sale, that’s not a bad idea, in my opinion, because sometimes it helps to hear things described by multiple people.

Note that production quality was not a consideration in my ranking, and some of the courses don’t have top notch sound quality. If that annoys you, perfect, write it down as an example of your anger to work on with the tools from the course.

I also evaluated one course that isn’t on udemy.com, it was on courseforanger.com. It says it satisfies court requirements, which I assume means a court ordering someone to take an anger management course for a certain number of hours. You pay different prices for the course based on how long you’re required to contemplate the material, from 4 to 16 hours. 4 hours costs $25, while 16 hours costs $85, but I believe the material in the course is the same. This was eye-opening to me because this was my least favorite course of the 12 I looked at, and it seems like it wouldn’t be particularly more useful after 16 hours with the course pages open versus 4. The course was all text, by the way, no videos, and personally I read through all the slides in a little over an hour.

In a future blog post, I’m planning on doing a ranking of Udemy courses on building self-esteem.

Apr. 15, 2022:

22 things you may say that destroy the most value in the world

In a previous blog post, I presented a ranking of some of the most value-destroying actions I think people can do, and, based on that, some of the most value-destroying words people can say. I then used that ranking to come up with a list of what I believe are 22 of the most value-destroying things everyday people say. These aren’t the most value-destroying things anyone says, since crime bosses may more directly destroy value with their words such as saying “shoot him,” and then someone does. I’m just considering everyday people here who may not realize the full extent of the value destruction they contribute to with their words. My goal isn’t to make you feel like a bad person if you say these things, it’s to try to make you aware of the potential damages of your words so you can decide for yourself if you want to continue to say them or not. Note that it can be difficult to assess relative levels of value destruction of different things people say because they depend to a significant degree on who the audience is, how much words may influence the audience and the speaker themselves, and the situation the words are used in. Therefore, my list is only very generally in order by expected level of value destruction. Also, there can be some variation in the exact words people use from the ones on this list – it’s more the theme of the dishonorable speech that’s important, I believe. Here, then, is my list of 22 of the most value-destroying things everyday people say:

- “They’re pure evil,” “What a scumbag,” “He’s such a jerk,” “They’re a monster,”- How it destroys value: it hurts reputations, dehumanizes, implies people are beyond rehabilitation, and makes violence against and stealing from them more likely

- “That’s inexcusable!” (also: unforgivable, unpardonable, indefensible, reprehensible, deplorable, insupportable, despicable, contemptible, disgraceful, and unjustifiable) – How it destroys value: it hurts reputations, dehumanizes people seen as abusers, and promotes victim mentality. It also generally hurts the speaker’s experience of life because it helps keep them in a state of anger rather than joy.

- “How could you?,” “You’re bad for saying that!,” “Have you no heart?,” “Have you no sense of shame?” – How it destroys value: shaming or trying to make someone feel guilty hurts reputations and encourages a victim mentality by painting someone as an abuser

- “They’re all a bunch of crooks” (about politicians), “You know the rich only care about getting richer” – How it destroys value: it hurts reputations and trust, misrepresents reality and relative levels of value, and discourages critical thinking and putting in effort

- “Where there’s smoke, there’s fire” – How it destroys value: it goes against critical thinking and hurts reputations by assuming guilt rather than innocence

- Gossip – How it destroys value: it hurts reputations, goes against one’s conscience

- Lying/misleading (by everyday people) – How it destroys value: it’s a form of cheating, and goes against one’s conscience

- “I’ll do that” (and then you don’t) = not keeping your word in non-life-threatening situations. How it destroys value: it’s a form of cheating and goes against one’s conscience

- “They should be made to pay!” (through violence), “He needs to have his butt kicked,” “They got what they deserved” (that is, some violence against them) – How it destroys value: it promotes violence

- “You should be outraged!,” “Doesn’t it bother you that?,” “I hate it when…,” – How it destroys value: it promotes anger and hate, making non-critical thinking and violence more likely

- “They’re stealing our jobs!” – How it destroys value: it promotes hate against a group of people, making stealing from and violence against them more likely

- “It’s so-and-so’s fault, not mine,” “It’s not my responsibility,” “Why doesn’t someone do something about this?,” “That’s not my job!,” “I’m mad at you!” (which basically says, “It’s your fault I’m mad”) – this is all blaming and not taking responsibility How it destroys value: it promotes stealing and violence. I see blame as a major tool of justification behind wars, murder, stealing, and other value destruction.

- “Can you believe these rich, middle-aged white guys are in a space race while people are dying of starvation? It’s morally wrong!” – How it destroys value: it encourages hate, discourages critical thinking and honest effort, can be a denial of the speaker’s own responsibility in people starving, and promotes entitlement

- “Their suffering is real!,” “You poor thing,” “My life is so miserable,” “You deserve a break,” – How it destroys value: it promotes a victim mentality, which lowers self-esteem, can be used to justify stealing, and generally encourages putting in less effort

- “They need it the most, so they should have it,” “If it’s so good, why does it cost so much? Why isn’t it free?” – How it destroys value: it promotes entitlement, misrepresents reality and relative levels of value, and is used to justify stealing and putting in less effort

- “They owe us” (when there’s no contract that says they do), “They (a business) should do something for the community” – How it destroys value: it supports entitlement, plus stealing by coercion

- “It’s not fair!,” “The wealthy need to pay their fair share!,” – How it destroys value: it supports entitlement, and stealing by coercion

- “You’re not good enough,” “You’re too stupid,” “Idiot!,” “You’re never going to amount to anything” – there’s no chance you’re gonna succeed, so you should stop trying – How it destroys value: it discourages effort, encourages victim mentality and a lower self-esteem, and it lowers the self-esteem of the person saying it because it supports putting others down as a temporary way to feel better about oneself

- “I’m not good enough,” “I can’t because…” – How it destroys value: it supports low self-esteem, and excuses are used to justify putting in less effort to build value

- “Nothing really matters,” “It doesn’t really matter if I do…,” – How it destroys value: it’s a denial of reality, of value, and of your responsibility and ability to affect things, if even in only apparently small ways, thus justifying putting in less effort

- “This is how it’s always been done” – How it destroys value: it goes against critical thinking and risk taking

- “That’s so bad for you” (with no explanation given as to why) – How it destroys value: it discourages critical thinking

And I’ll just add one more as a bonus, which could perhaps be considered as 18b:

18b. “People are so f-ing stupid!” – How it destroys value: it discourages critical thinking and empathy, and lowers the self-esteem of the person saying it because it supports looking down on others as a temporary way to feel better about oneself.

Since my website is called dishonorablespeechinpolitics.com, I’d like to point out some items on this list that seem to be commonly communicated to the public by politicians: #12 “It’s so-and-so’s fault” (generally the other political party’s), #14 “Their suffering is real!” (and we’re the ones coming to save them), #17 “It’s not fair!,” #1 “They’re pure evil,” #9 “They should be made to pay” (through violence), #10 “You should be outraged!,” #8 “I’ll do that” (and then they don’t), #7 lying/misleading, #11 “They’re stealing our jobs!,” and #2 “That’s inexcusable!”

That’s my list of 22 things everyday people say that I believe are some of the most value destroying. I hope by becoming more aware of them, you may be inspired to choose your words differently in the future so as to avoid unnecessary value destruction.

Apr. 13, 2022 (edited Apr. 17, 2022):

Ranking actions and words by how much value they destroy

This blog post is the result, in part, of me trying to figure out what I want to do with the rest of my life. Maybe you can relate. I care about things like there being less war and violence and stealing in the world, and people being happier and healthier. So I asked myself, what could I do with my remaining time on this Earth to try to have the biggest positive impact, which may, in fact, involve helping to avoid the most negative things? To answer this question, it seemed like it’d be useful to better understand what sorts of things destroy the most value in the world. So for this video, I tried to rank value-destroying actions and inactions by how much value they destroy. A most value-building actions list will have to wait for another time. Having a ranked list of value-destroying actions also helped me get to a ranked list of value-destroying speech, which I used to construct my list of 22 of the most destructive things everyday people say, to be presented in a future blog post.

But what do I mean by “value” when I say “value destroying?” I define value as usefulness to people in ultimately supporting and promoting life, supporting people’s individual rights to their own lives and the products of their efforts, and in gaining “positive” experiences, where “positive” can be objective, such as if it helps avoid death, or subjective, such as the positive experience you get from a keepsake that means something to you, but not someone else. So if you care about life, basic human rights, and positive experiences for yourself and others, you probably care about value being built rather than destroyed. And, conveniently, I define dishonorable speech basically as speech that helps motivate value destruction and/or directly destroys value. So if you’re a value lover like me, you probably want to avoid dishonorable speech as much as you can.

In making my list of most to least value-destroying actions, I considered people’s rights to their own lives as of the greatest value, then their rights to the products of their efforts, then human life in general, and, finally, generally of least value, positive experiences. I didn’t include the value of animal life, but if I had, I would’ve put it above positive experiences and below human life. I put people’s rights to their lives and property as of highest value in part because I believe these are foundational to value building. What I mean by that is, in certain situations, violating rights may seem to result in the most value in the short-term, such as seizing one person’s land to build a highway for many, but I believe in the long-term this violation generally results in a greater overall value loss. The way I see it, much more value is built when people can trust each other and work together than when they can’t. If I can’t trust that my rights will be respected in all but the most extreme cases, then I’m less likely to put in the effort and work with others to build value. Also, when we violate rights, there’s a value destruction in our own experience of life because we’ve gone against our conscience, assuming we have one. It may be easier to intuitively grasp how important rights are if you think about how it feels when yours are the ones being violated.

Coming back to my list of value-destroying actions, actions can be physical, including communicating words, as well as mental, including thinking and feeling. I’ll exclude communicating words from this first list and include it in its own list in a minute. Also, this ranked list of actions is only a general guideline, I don’t assert that it’s complete or that the order of the items is absolute. Finally, I got some ideas for my list by reading multiple blog posts by Michael Huemer at fakenous.net, as well as his “Knowledge, Reality, and Value” book, and by reading Peter Singer’s book “The Life You Can Save.” Both Huemer and Singer are philosophy professors, but with some significant differences of opinion, and I recommend reading both of their works because they make you think, or at least they did for me.

With that, my list of most to least value-destroying actions or inactions is:

- Committing murder (a person intentionally killing another, without their permission, and not in self-defense)

- Torturing someone

- Being physically violent towards someone (not in self-defense), resulting in long-term health issues

- Unjustly imprisoning or punishing someone (which also can involve damage to their reputation, and financial loss)

- Coercing someone – forcing someone (in a non-defensive situation) to do something under threat of violence

- Emotionally “abusing” a child such as contributing to them feeling like they’re not good enough to be loved

- Polluting – negatively affecting people’s health, shortening lifespans

- Being physically violent towards someone (not in self-defense), resulting in no long-term health issues

- Damaging/destroying property (without the owner’s permission)

- Stealing, which includes cheating, a form of stealing, such as in business or sports

- Going against one’s conscience, including hating, resulting in a less positive experience of life, and making future value-destroying actions more likely if one suppresses their conscience rather than feels the full pain of it – note that this value destruction is on top of the external value destruction of the act itself, such as murdering someone

- Not taking responsibility for one’s actions and emotions, thus lowering one’s self-esteem – this includes blaming (in one’s mind), lacking gratitude, and feeling entitled or like a victim

- Acting without critically thinking about the ethical consequences, when one has time to think things through in advance

- Not holding people accountable for their destructive actions, i.e., not upholding justice

- Committing suicide

- Not taking care of one’s health, both physical and mental (this includes doing risky things and not preparing for possible disasters)

- Not helping when one could (i.e., without affecting one’s health or bringing about other significant value destruction) to save someone’s life or avoid them having long-term health issues

- Not helping when one could to give others and oneself positive experiences, such as losing out on human connection by avoiding interacting with others

- Not maximizing productivity (resulting in a loss in the expansion of options for positive experiences), including not pushing against one’s comfort to take on challenges or put in effort towards goals

- Damaging/destroying one’s own property, or someone else’s, with their permission

In addition to these value-destroying actions, there can be value destruction in actively helping someone do them or get away with doing them. Also, some of the actions on this list can have a large range of possible value destructions. For instance, if someone’s murdered 10 seconds before they were going to die anyway, that could be considered to result in significantly less value destruction than if someone’s murdered who likely had 60 good years left to live. So again, the order of my list is just a general guideline, it’s not meant to be absolute.